This is Part 1 of a series. Read the other parts here: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5

New Amsterdam Stories:

The Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam implemented its city charter on February 2, 1653 (Candlemas Day), the traditional swearing-in day of Dutch city officials. On this day the Records of New Amsterdam begin, and on February 10th, the Burgomasters and Schepens, roughly equivalent to our Mayor and City Council, held their first formal meeting. The New York City Municipal Archives has digitized the records of those meetings and put them online. Translated and published in the 1800s, it has been 100 years since these original Dutch records were made accessible to scholars. One fascinating aspect of using original source materials is that you see history being made, and feel a direct line to the decision makers of the past. This is the first in a series of posts exploring what those court records reveal, and we hope the start of exciting new scholarship.

Good Fences, a History of Wall Street

Sometimes a wall can become a rabbit hole. I started with the intent to write a simple post that would answer three questions: What was "the Wall"? Why was it built? When did the name Wall Street come into use? As is often the case when digging into history, there were no simple answers, and my research (after sidetracks into European and frontier fortifications, nuances of obscure 17th-century Dutch words, and the history of New Amsterdam maps) led to some surprising and forgotten knowledge about New Amsterdam.

An illustration of the wall from the 1800s, about 200 years after it came down. From Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments. Augustine E. Costello, 1887

Many people could tell you that Wall Street received its name from the stockade fence that protected the northern edge of New Amsterdam, but persistent myths survive: the wall was built to protect inhabitants from Native Americans, it was a crude structure, the street was called Waal Straat by the Dutch, or it was only named Wall Street after the wall was removed. A new myth is currently spreading online: Hollanders think the street name is derived from a slang word for French-speaking Walloons. In reality, none of these are true, but the history is so complicated it will take a few posts to unravel. Let us start with the simplest question: Why was the Wall built?

In 1653, the Dutch and English were in the midst of the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654). In New England, English troops were amassing and rumors of this reached the small colony of New Amsterdam. Against this backdrop New Amsterdam formed its first city government. Soon after, on March 13, 1653, an emergency meeting brought together the Director General (Petrus Stuyvesant), his Council, and the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens. The following point was discussed:

Upon reading the letters from the Lords Directors [of the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam] and the last received current news from New England concerning the preparations there for either defense or attack, which is unknown to us, it is generally resolved:

First. The burghers [a type of citizen] of this City shall stand guard in full squads over night…

Second. It is considered highly necessary, that Fort Amsterdam be repaired and strengthened.

Third. Considering said Fort Amsterdam cannot hold all the inhabitants nor defend all the houses and dwellings in the City, it is deemed necessary to surround the greater part of the City with a high stockade and a small breastwork….”

They also resolved to raise money for defense and to arm a ship for war in the harbor. The following day they deliberated over the exact nature of the defenses and taxes to pay for them (the question of who should pay for the wall would become a continual point of discussion in the records). They also agreed to send representatives to the “Colonies of New England, our neighbors” to express their desire for “continuation of our former intercourse and commerce” despite the “differences and the war in Europe.”

“The Castello Plan” of New Amsterdam shows the wall as it was circa 1660. Reproduced from the Iconography of Manhattan Island, I.N. Phelps Stokes, 1915.

From March 13th - 16th, five pages of minutes depict the representatives’ discussion of the threat of war with the English and the need to build a wall. They even list the names and amounts of all the citizens who would contribute to the defense. Not one mention of Native Americans. From March 17th - 19th the “Committee appointed for the work of making this City of New Amsterdam defensible” met to discuss logistics, cost, posts, lumber, and nails, and to hear bids for the work. “The palisades must be 12 feet long, 18 inches in circumference, sharpened at the upper end and be set in line. At each rod a post 21 inches in circumference is to be set, to which rails, split for this use shall be nailed one foot below the top. The breastwork against it shall be 4 feet high, 4 feet at the bottom and 3 feet at top, covered with sods, with a ditch 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep, 2 ½ feet within the breastwork… Payments will be made weekly in good wampum.” They helpfully included a schematic drawing in the margin.

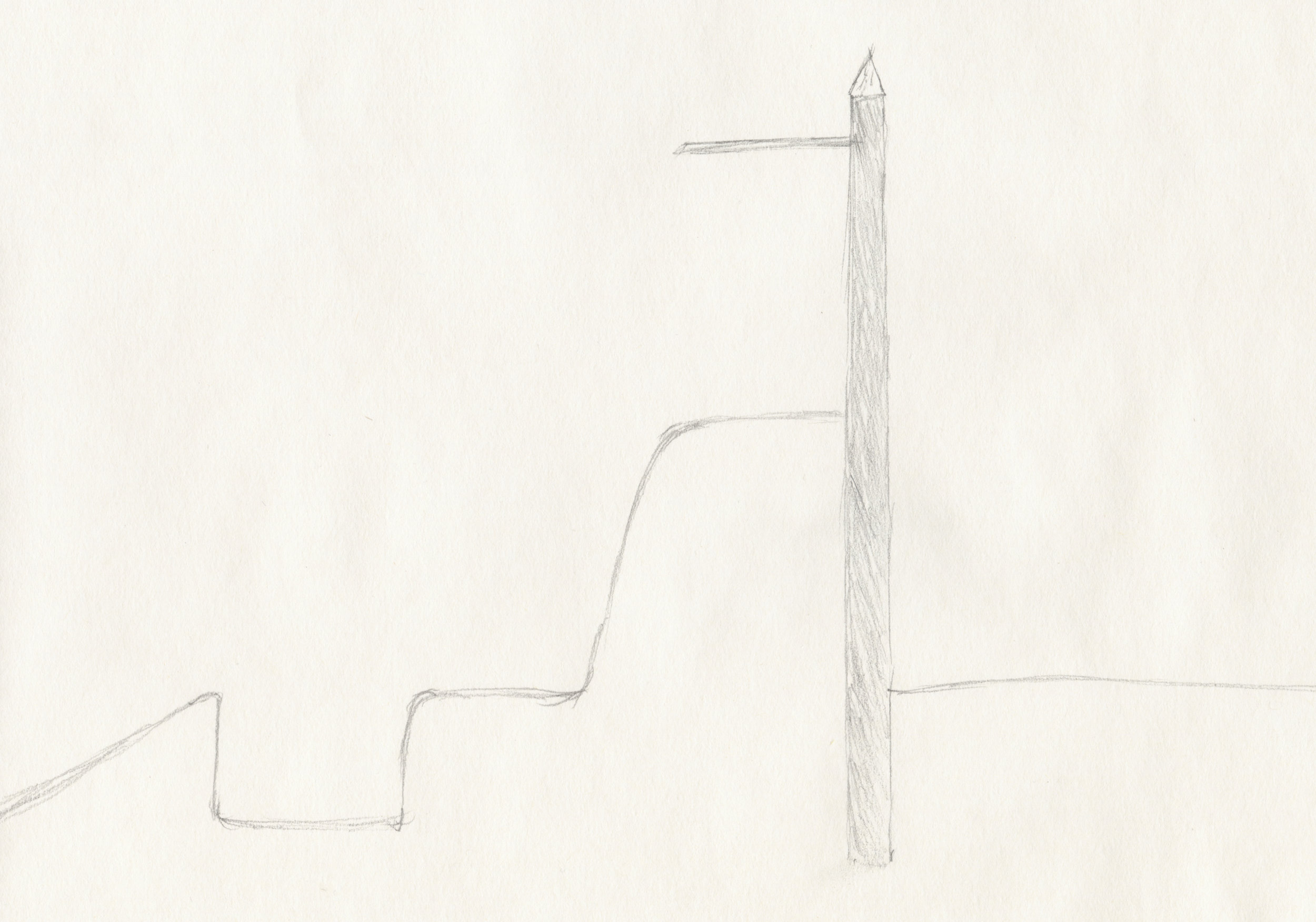

Diagrammed cross-section of proposed wall from the Court Minutes of New Amsterdam, March 17, 1653. The exterior has an embankment and a ditch, and the line projecting from the top of the wall may be a fraise, small sharp sticks to impede scaling the wall. The Dutch reads: “9 feet above ground, 3 feet in ground.” One dot = one foot.

Illustration to scale (according to measurements in court records) by author. In the end, this version proved too expensive, and a simplified version was constructed, but with a much larger ditch.

In true municipal government fashion, the work was put out to bid:

Notice: The Committee… will receive proposals for a certain piece of work to set off the City with palisades, 12 to 13 feet long… Any one who wishes to undertake this work may come to the City Hall next Tuesday afternoon, hear the conditions and look over the work.

But nobody would do the work for the price the committee had in mind, so the plan was revised. The new plan called for plank wall sections 15 x 9 feet, attached to posts. The expenses for materials and labor were calculated and a new bid went out. By March 20th Thomas Baxter agreed to the terms. Work began almost immediately, carried out by a combination of enslaved and free labor. Although slaves surely did a lot of the heavy lifting, in April it was ordered that “the citizens without exception, shall work on the constructions… by immediately digging a ditch from the East River to the North River, 4 to 5 feet deep and 11 to 12 feet wide.” And that “the soldiers and other servants of the Company, together with the free Negroes, no one excepted, shall complete the work on the fort by constructing a breastwork, and the farmers are to be summoned to haul the sod” (Gehring, New York Historical Manuscripts V., p. 69). By July 28th, the Council was able to report that “the City has, to the satisfaction and for the security of the inhabitants, been surrounded with palisades on the land side and along the Strand on the East River… done now already three weeks.”

The calculated cost of the wall, "180 rods make 2340 feet, 15 feet to the plank make 156 planks in length, 9 planks high, altogether 1404 planks at 1.5 guilders, that is 2106 guilders." Plus "340 posts cost 340 gl." "nails 100 gl." "for transport and setting them up... 120 gl." and "carpenters wages... 500 gl." For a total cost of 3166 gl.

In May representatives of the English colonies came to Fort Amsterdam not to meet with the Dutch, but to interrogate Stuyvesant regarding rumored Dutch plots to incite the Native Americans against the English. They left the next day in somewhat of a huff, warning the Dutch and Indians to stay out of English affairs. The First Anglo-Dutch War ended in 1654 without spilling over into the colonies in a significant manner. The one lasting reminder of the war in New Amsterdam was the Wall.

Given overwhelming evidence that the Wall was constructed because of the very real and present danger of the English, why does common knowledge hold that the Wall was built to protect against Native American attacks? A simple answer may be that victors write history. When the English did take control of the area, they may not have wanted to be seen as the aggressors in this story. However, the truth may again be a bit more complicated. The Wall was not just one wall. It was altered many times during its 46-year existence and its purpose often depended on who was on the inside versus who was on the outside. In 1655, following a brief war with native tribes known as the Peach Tree War, Stuyvesant did order the wall be extended and improved to better defend against such attacks. However, this was just part of the continuing history of a wall that would become intractably linked to the English and the history of America.

Next time: Walls, Wals, Waals and Streets - what’s in a name?

Special thanks to Dennis Maika and Charles Gehring at the New Netherland Institute and Ellen Fleurbaay and Harmen Snel at the Stadsarchief Amsterdam for help with translations and other feedback.

Except where noted the English translations of the Dutch records are from Fernow: Records of New Amsterdam.

Visit newamsterdamstories.archives.nyc to learn more.