In late October 2023, the Department of Records and Information Services and the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority opened a new exhibit: “Uniting the Boroughs, The TriBorough Bridge.” Consisting of images from the archives at both agencies, the exhibit showcases the twenty-year project to build the bridge.

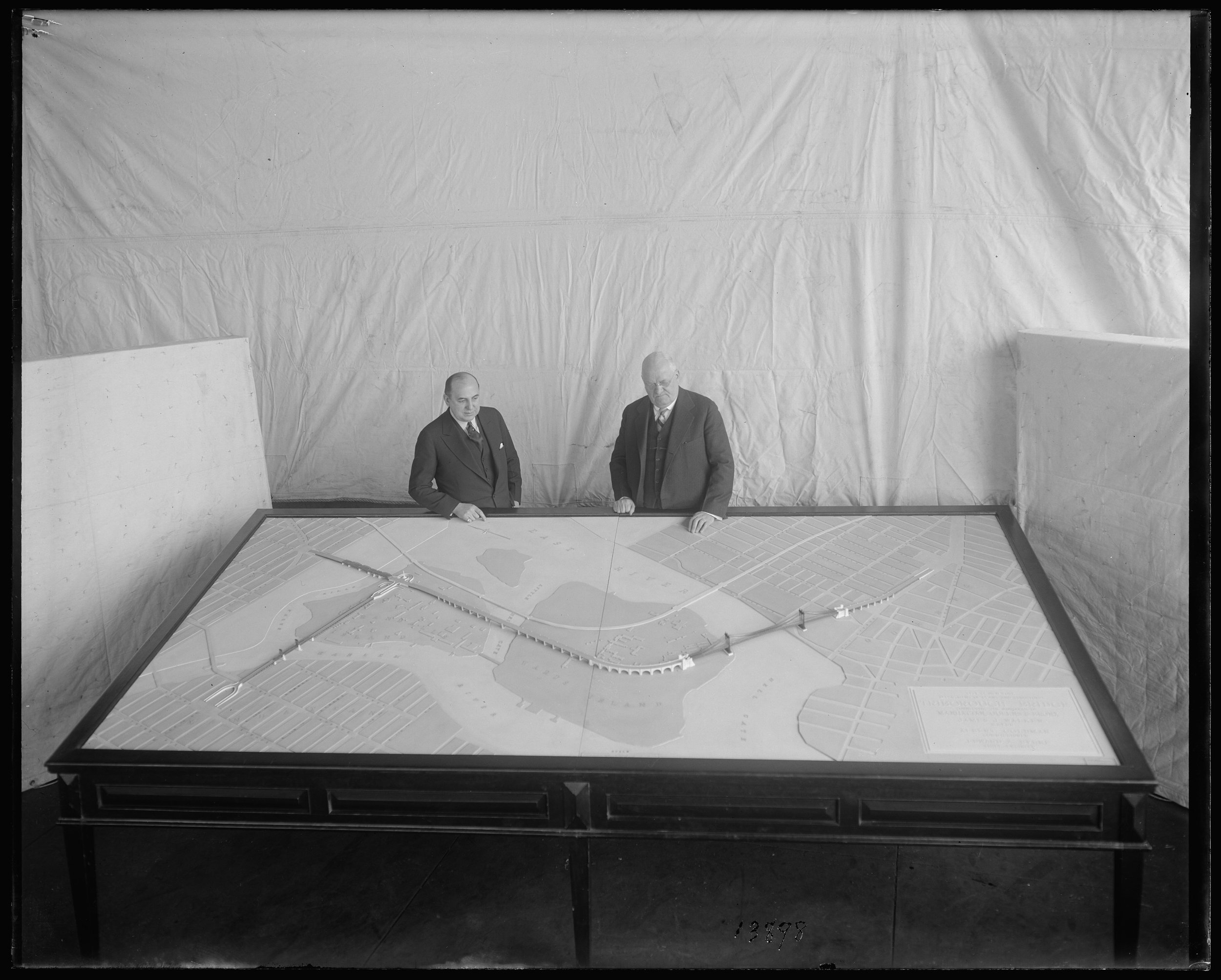

Tri Boro Bridge model, chief and commissioner, February 4, 1931. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Edward A. Byrne the chief engineer of the Bridges Department of the New York City Department of Plant and Structures (DPS) initially proposed the bridge in 1916. The bridge was supposed to connect rapid transit lines between the boroughs and “provide for vehicular and pedestrian traffic as well as for a double track surface railway.” It was a very ambitious engineering feat with multiple types of bridges: a suspension bridge over the East River; a cantilever span at Hells Gate Channel; and a draw bridge between Randall’s Island and Manhattan’s 125th Street with “the opening for navigation purposes…made by a lift span instead of swing span.” The cost for the entire structure, including labor and materials was estimated at $10.5 million.

Figures in the DPS 1916 annual report showed that 9,858 vehicles crossed the Queensborough Bridge during the “daily count.” By 1922, this Daily Peak Load had increased to 14,638 vehicles. Additionally, on average, 942 daily passengers traveled by ferry between the Bronx and Queens and 4,629 passengers took ferries from Queens to Manhattan, daily.

Some saw the bridge as a panacea that would improve living conditions in the City. A 1924 article in the Harlem Board of Commerce journal reports several advantages:

“It is one of the solutions to the traffic conditions that are today conceded to be one of the city’s most serious problems.

It would materially assist in bringing to an end the present housing shortage by developing large areas…

It would enable the farmers of long Island to bring their produce to the consumer in less time and at less cost than is possible at present.”

The proposal languished until 1927 when the Board of Estimate appropriated $150,000 to conduct surveys and borings for the bridge which it was hoped would reduce traffic congestion. DPS Commissioner Albert Goldman explained the reasoning for selecting 125th Street in Manhattan as the terminus for that borough. It was “the first street north of 59th Street that might be considered a river to river highway. Central Park divides the Borough of Manhattan, north and south, between 59th Street and 110th Street and between these streets in the park there are a few narrow winding transverse roads quite inadequate for present day vehicular traffic.” The estimated cost for the entire 17-mile connection had increased to $24,625,000.

Tri Boro Bridge, views of buildings for condemnation, Astoria: 2705 Hoyt Avenue, January 9, 1931. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Tri Boro Bridge, views of buildings for condemnation, Astoria: Hoyt Avenue number 2907 and 2905, March 6, 1931. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Tri Boro Bridge, views of buildings for condemnation; 2472 to 2466 24th Street front, November 11, 1930. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

In June 1929, the Board of Estimate allocated $3 million to begin work on the bridge and the City began soliciting bids and identifying property to condemn, with the hope that construction would be completed within four years. A ground-breaking ceremony was held in Astoria Park on Friday, October 25, 1929, a date known widely as “Black Friday,” the day the stock market crashed, beginning the Great Depression. Before the consequences of Black Friday became clear, the Queens Chamber of Commerce enthusiastically celebrated the project’s launch as marking “an epoch in the history of the borough comparable to the breaking of ground for the Queensboro Bridge on July 19, 1901, and the inauguration of rapid transit operation in the borough in 1915.”

As late as February, 1930 optimism prevailed. “Work on Tri-borough Bridge Progressing Rapidly” a Harlem Magazine headline trumpeted. They reported that foundation work on Wards Island was underway and forecast breaking ground on the Harlem portion in May, 1930. Instead, construction stalled again.

Tri Boro Bridge Wards Island showing steel construction and piers, December 1, 1931. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Tri Boro Bridge party of engineers on inspection, December 19, 1931. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

By March 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, there were 13 million unemployed Americans. The financial and banking sectors had ground to a halt. Manufacturing of all types had slowed considerably. Roosevelt announced an ambitious agenda to get America working again. In the first 100 days of his administration, banking reforms were initiated and public works programs were funded to build infrastructure and put people to work. One of the most important was the Public Works Administration (PWA) which directly funded the construction of roads, bridges, tunnels and subways to the tune of $4 billion during the course of its existence—the equivalent of just over $113 billion today. This included $44 million in grants and loans for the Triborough Bridge. The PWA was headed by Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior and good friend, Harold Ickes.

Tri Boro Bridge showing anchorage and masonry, February 9, 1932. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

In 1933, the President’s ally, New York State Governor Herbert H. Lehman issued a message in support of legislation to create a three-member Triborough Bridge Authority (TBA) to oversee construction. He noted, “The completion of the Triborough Bridge is regarded as one of the most important public works in this state. It is of vital interest to the City of New York, and, in fact, to the entire metropolitan district.” The bridge was to be a “self-liquidating project,” meaning that when the costs were recovered, tolls would cease. As drivers today can attest, that was not to be the case.

In January, 1934, Fiorello LaGuardia took office as Mayor of New York City. He embraced the New Deal programs and City projects quickly received federal funding. The three-person TBA included the City’s Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses who was known for making things happen. LaGuardia made Moses the Executive Director. The TBA applied for funding and the PWA awarded $9 million in direct funding and a $35million loan for the bridge. Construction resumed. People were working. The project was said to have involved “600 manufacturing plants in thirty states….” providing “2,000,000 cubic yards of concrete. Ninety-one thousand tons of steel and iron products were produced in the mills and shops of thirteen states more than 200 contractors, who at times gave work to 3,000 men on the project were employed,” according to engineer Othmar H. Amann. And then... drama!

Surprisingly, in 1934 Moses challenged Lehman in the State’s race for Governor. During the course of the campaign, Moses heaped abuse on the New Deal programs and called its supporters frauds. Lehman trounced Moses who returned to his roles at the TBA and the Parks Department. The challenge to Lehman and the comments about the New Deal programs had infuriated the President.

Tri Boro Bridge Astoria Park view showing sign: anchorage, March 16, 1932. Eugene de Salignac, photographer, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

In January, 1935 PWA head Ickes issued an Administrative Order that prohibited PWA funding to municipalities that had recipient organizations headed by people employed elsewhere in municipal government. The order threatened $300 million for a variety of public works projects in New York City. Ostensibly an effort to reduce cronyism, this was seen as an attempt to get back at Moses. It was widely reported that the Order only applied to two people: Moses and the Tenement House Commissioner, Langdon W. Post. The Mayor attempted to follow the order but Moses would not relinquish either of his positions. When asked about how the order would affect Post, the New York Times reports the Mayor said, “At least Post is on the high seas, and he can’t issue any statements… His answer was construed as a slap at Mr. Moses for bringing the dispute into the open after the Mayor had sought to cover it over with the declaration that no friction existed.”

Moses wouldn’t leave and eventually Mayor LaGuardia and the President resolved the dispute making the order applicable to individuals appointed after it was issued, thus preserving both Moses and Post in their positions. But, this did not reduce the acrimony between the President and Parks Commissioner Moses. In April 1935, Ickes inspected the Triborough Bridge construction, “accompanied by representatives of the Parks Department and the Triborough Bridge Authority, but Robert Moses, whose ousting from the Authority was sought so vigorously for several months last Winter by Mr. Ickes, was not among them,” the Times reported. As late as October 1935, Moses was attacking the New Deal policies in the Saturday Evening Post.

Triborough Bridge construction, Randall’s Island, February 10, 1936. Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority Archive.

The project employed thousands of workers and work continued around the clock. “The project makes light of any obstacle in its path. City blocks vanish. Narrow streets are widened as if a titanic wedge were hammered through them between their confining house walls. Creeks surrender to concrete arches. Piers rise for a approaches to bridges that will set arms of the sea at naught, even deadly Hell Gate, wrote reporter L. H. Robbins.

Finally, the long-awaited opening was scheduled for July 11, 1936. Toll booths were completed the day before. Supports were removed. Painters completed their work overnight. Three thousand people attended the opening held on the hottest day of that year.

Telegram, July 2, 1936. Correspondence with Federal Officials, Mayor LaGuardia Records Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

There was some concern that antagonisms might arise at the event. Mayor La Guardia sent a telegram to Ickes, appealing that he attend the event. Robert Moses presided at the opening, introducing all of the speakers, including President Roosevelt and Harold Ickes. In his remarks, Moses said that projects as important as the Triborough were “too big for personal enmities.”

Never one to block a metaphor, at the opening Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia praised the construction as offering employment during the depression and questioned, “What could be more symbolic of our present-day efforts than a bridge? Are we not seeking to bridge our present troubles? Is this not a monument to the determination of the American people today, and a reminder of the mistakes of the past?”

Robert Moses speaking at Opening Day ceremonies, July 11, 1936. Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority Archive.

In his remarks, President Roosevelt thanked the workers on the bridge “and those workers in the mills and shops many miles distant, without whose strong arms, willing hands and clear heads there would be no celebration here today.” He praised the construction of the bridge as the response of a modern government to the evolving needs of the population. “People require and people are demanding up-to-date government tin place of antiquated government, just as they are requiring and demanding Triborough Bridges in the place of ancient ferries.” He also took a swipe at critics, possibly even Moses, “There are a few among us, luckily only a few, who still, consciously or unconsciously, live in a state of constant protest against the daily processes of meeting modern needs. Most of us, I am glad to say, are willing to recognize change and to give it reasonable and constant help.”

Tri Boro Bridge, 125th Street, Manhattan, March 11, 1937. Photographer unknown, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

“While the speeches were in progress motorists by the thousands gathered at the Manhattan, Bronx and Queens approaches of the bridge, waiting to be among the first to cross the structure.” reported the Herald Tribune. The headline proclaimed “11,100 tolls paid in first hour rush.”

Tri Boro Bridge general view, January 11, 1937. Photographer unknown, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.