As has often been stated, the Covid 19 pandemic has yielded the worst economic situation since the Great Depression. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that unemployment now hovers just under 8%, after reaching a high of 14.7 % in April 2020. At the peak of the Depression, however, national unemployment reached a high of 25% by 1933 and one third of New York City workers were unemployed. In his book, The Lean Years, Irving Bernstein provides data from the federal Committee on Economic Security showing that the number of unemployed workers increased from 429,000 in October 1929, to 4,065,000 in January 1930. By October 1931 nine million Americans were out of work.

Frequently, in discussing how NYC fought back during the Depression, the focus turns to Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. But, he wasn’t the Mayor at the inception of the Depression. Instead it was James Walker, the so-called “Beau James” due to his spiffy clothes and nighttime gallivanting. Elected in 1925 with the help of former Governor Al Smith and the Tammany machine, Walker defeated incumbent Mayor John Hylan. Walker styled himself as the “people’s mayor”—he relied on publicity and wit, not policy or good government. Yet some observers of City government have described him as a decisive problem solver. He did oversee revisions to the Building Code and the City’s tax structure. But, it was his public persona that people liked. Opposed to Prohibition, he once staged a “We Want Beer” event in 1932 attended by 100,000 people. In 1929 he ran for re-election, beating the Republican candidate—LaGuardia--handily. Walker resigned in 1932 after a corruption inquiry revealed many “beneficences” given to him by City contractors.

Mayor James J. Walker, seated at left, and film actress Marjorie King at the Motion Picture Club Ball, Waldorf Astoria, February 1932. Municipal Archives Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Walker was in the hot seat when the stock market crashed in October 1929. Today, we are used to a centralized government that focuses resources on city problems but as Warren Moscow long-time New York Times reporter wrote in a 1976 reflection on Depression-era government. “there were no central departments of Highways, or Public Works. The city Street Cleaning Department did not extend to Queens and Richmond, where the Borough Presidents appointed their own men to lean on brooms. There were five separate Park Departments and no Department of Traffic, although the police were beginning to restrict some side‐streets, but not avenues, to one‐way use.” Although Walker created the Department of Hospitals which put all of the municipal hospitals under one charge and developed large-scale construction projects such as the TriBorough Bridge and the West Side Highway, City government did not have a mechanism to provide large-scale relief. At this point, unemployment insurance didn’t exist anywhere in the United States. New York City, like all other municipalities relied on a patchwork of philanthropic and charitable societies to provide assistance to the poor, the unemployed, the homeless and the hungry, with those most indigent sent to almshouses. Despite valiant efforts, the Depression would change that system.

Known as “Hoovervilles,” large makeshift encampments of unemployed and homeless New Yorkers began to appear around the city during the Great Depression. Red Hook, Brooklyn, ca. 1931. Municipal Archives Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

In March 1930, the New York Times reported that 35,000 people protested unemployment in the City as part of an International Unemployment Day by the Communist Party. Protesters marched toward City Hall only to be violently stopped by police officers.

Also in March, a coalition of trade union leaders wrote the Mayor with proposals that “will bring an immediate measure of relief.” They focused on public works; creating a system to provide direct relief and a process for finding work without paying private employment agencies. In doing so, they noted that the City’s public works program fell short and that “rather than a speeding up of public works an actual recession in the letting of contracts has been the case.” They cited the reduction in contracts for subway construction, the lack of funding for slum clearance and housing construction and the lack of a system to provide relief. “Daily reports reveal that the private welfare agencies are swamped with requests for assistance. In the meantime, the Department of Public Welfare, which has as its chief function the relief of the destitute, has no funds available to meet this emergency. In fact, it is the practice of the department to shift applications for relief to the private charity agencies which have publicly stated their inability to meet the heavy demands being made on them. The responsibility of the city towards its workers demands not charity but that the city provide immediate relief for the jobless who are in dire straits through no fault of their own. It would be a lasting disgrace if in the richest city of the world a single man, woman or child should go hungry.”

The Department of Public Welfare operated a Lodging House on the Pier at East 25th Street, November 22, 1930. Photographer: Eugene de Salignac. Department of Bridges, Plant & Structures Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

A report from the Welfare Council of New York City discussed the pressure on the city’s employment and welfare agencies noting there was “a serious falling off in placement of workers in jobs and a corresponding increase in the number of homeless men, seamen and families applying for assistance.” The report also discussed “the disastrous consequences” for the unemployed and their families. “Constant anxiety and undernourishment bring suffering to the worker and his family. Undermining of physique and the loss of self-respect which accompanies weeks of fruitless search for work gradually bring mental and moral degeneration, and from being merely unemployed the worker becomes unemployable. His troubles do not cease when a job is found. The physical and mental deterioration consequent upon a long period of unemployment, a lowered standard of living and the burden of accumulated debt are long continued.”

Initially, data was unreliable and incomplete. In the April 23, 1930 edition of “Library Notes” a publication of the City’s Municipal Library, Rebecca Rankin wrote about the difficulty in obtaining accurate figures of how many people had been affected. “Owing to the inaccuracy and incompleteness of any figures available on unemployment at any one time, there seems to be some doubt as to whether times are as bad as portrayed.”

W.E.B. DuBois wrote Mayor Walker in 1931 asking for “information as to what was accomplished for the relief of unemployed Negroes last year in New York and what plans you have for the coming year.“ The response from the City was that relief funds were not segregated by race and further, that if the information could now be obtained by investigation, it does not seem to me desirable to obtain it.”

The impact of the Crash is not initially apparent in the correspondence of the Department of Welfare. But by June 1930, the Mayor and other officials were receiving letters requesting assistance. Welfare Department Commissioner Frank J. Taylor wrote several acknowledgements to the Secretary to the Mayor, Charles S. Hand. Invariably they would begin, “I am in receipt of your letter of the (date) instant enclosing a communication from…

Mrs. Mary Streppone in which she complains that family is in destitute condition and husband is out of work…

Manuel Manzano, who states that he was hurt while employed by the U. S. Electrical Mfg Corp…and desires assistance in his case with the Bureau of Workmen’s Compensation, as he is penniless and sick with a wife and three children dependent upon him…

Edward Reynolds, relative to his mother and her application for pensions for five of her grandchildren, whose parents are dead. …

Max Warsinger who is badly in need of help and requests some kind of work…

In all cases, Taylor promised that a representative from the Department would visit the writers to see if there is something to be done “to help them out.” The end result is not summarized in the files.

Richmond Borough President John Lynch to Mayor’s Committee Secretary McAndrews regarding contractors, telegram, November 20, 1930. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor’s Committee Secretary McAndrews request to Brooklyn Borough President regarding contractors, telegram, November 19, 1930. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

In October 1930, Mayor Walker created the Mayor’s Official Committee for Relief of the Unemployed and Needy which consisted of himself as the Chair, the Commissioner of the Department of Public Welfare, Frank J. Taylor as the Vice Chair, the City Chamberlain, Charles A. Buckley was treasurer, and the secretary to the Mayor, Thomas F. McAndrews was the Secretary. A slew of other city officials were listed as members. In the announcement he said, “The first cold spell that falls on this city is going to find a terrible condition. I want to be prepared for it. I want to feel that during it and after it, this administration, this group of men that make up this administration, have not left a thing undone that they could have brought about as a contribution to the alleviation of any suffering that will be found in this city.“

By November 1930, American City, a monthly magazine providing policy, equipment and other advice to city leasers reported on how cities were tackling unemployment. New York had a lot going on: “A City Employment Bureau is functioning; a police census of unemployed is in progress; the eviction of needy families for non-payment of rent is being halted; the police and other employees are arranging to donate extensively to unemployment relief; Mayor Walker has appointed a Cabinet Committee on Unemployment to deal with questions of food, clothing, jobs and rent; municipal lodging facilities are being added to. At the same time an effort is being made to prevent a flood of unemployed men from pouring in upon the city.”

The New York Life Insurance Company donated space to be used as the committee’s headquarters. The Committee drew upon eighty-one City workers assigned by departments as diverse as Transportation, Fire, Law, Police Tenement House among others. Salaries were paid by the originating agencies, thus reducing the operating costs of the Committee. The Police Department received a special acknowledgement in the 1931 report. “The members of the Police Department unstintingly gave of their personal time and energy in the field as investigators and reporters for the Committee. During the long hours of the night, patrolmen in the seventy-seven precincts packed and wrapped food packages. Even on Sundays, they prepared for the coming weekly distribution of food. The Welfare or Crime Prevention Bureaus of the police precincts coordinated in the work with the patrolmen on post.”

Five Months of City Aid for its Unemployed, 1931. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

In its first eight months, the Committee raised roughly $1.626 million and paid out $1.487 million according to a report on its activities through June 30, 1931. Nearly 11,000 families had been paid direct monetary relief. Eighteen thousand tons of food was distributed to close to a million families including a Kosher distribution to 6,000 families for the religious holidays. Other disbursements were for coal, shoes, clothing and a donation to the City of Utica for their unemployed. In the same period, the Welfare Council spent more than $12 million for relief and emergency work wages, all raised through voluntary contributions.

Was there any reason to worry, given the daily contributions received in City offices, earmarked for the unemployed and relief? While sceptics might question if any of the funds were skimmed, the accounts from the committee clearly show the amounts received and disbursed. The largest source of funds was from city workers who donated 1% of salaries to help the City’s needy, yielding $1.56 million of the money raised. Other sectors also contributed. Sports teams held matches and games. The Notre Dame football team played the New York Giants, raising $115,153 for the fund. Broadway also stepped up staging nineteen performances that raised nearly $18,000.

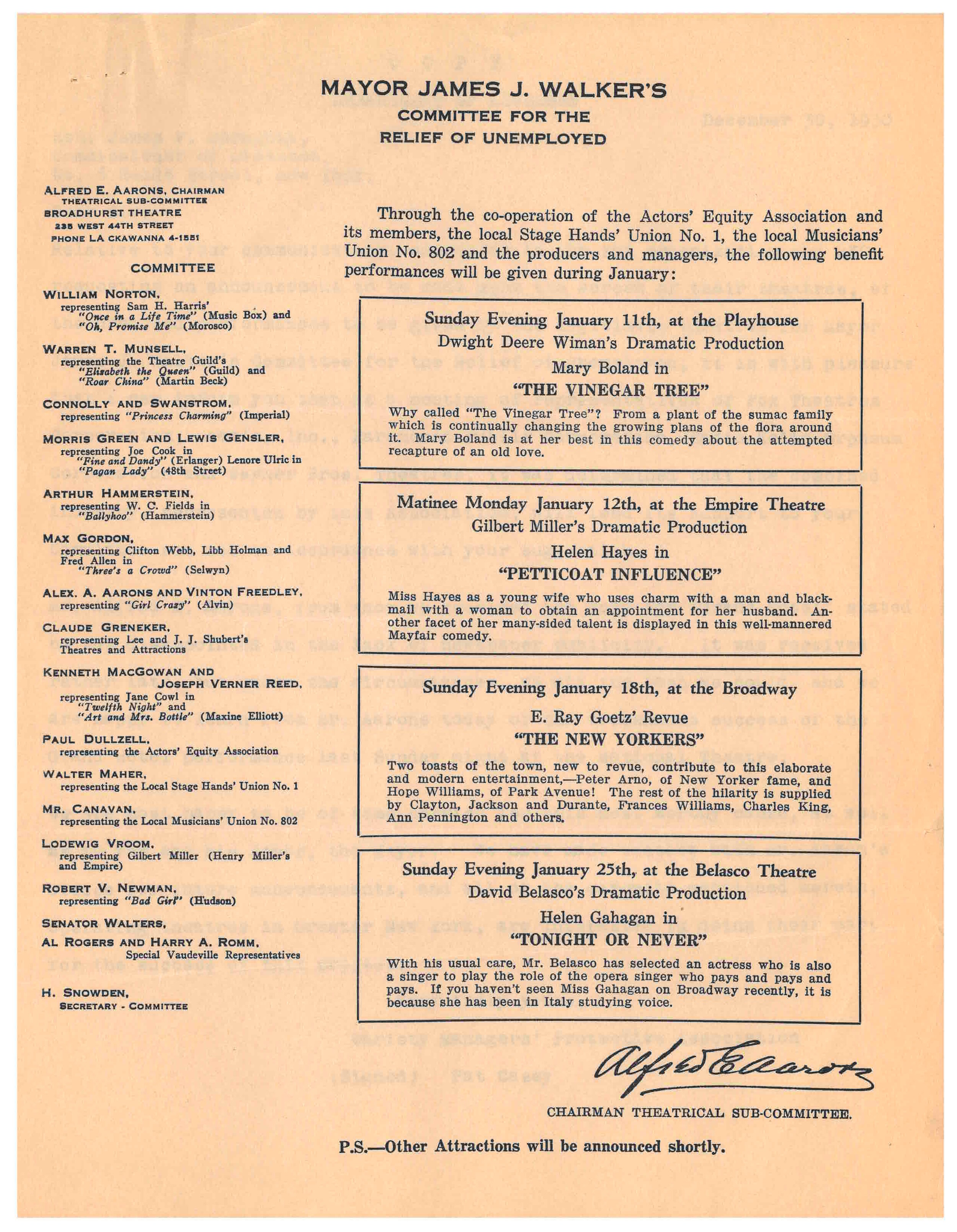

Mayor James J. Walker’s Committee for the Relief of Unemployed. Schedule of Benefit Performances through the co-operation of the Actors’ Equity Association, 1931. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

Any notion that the times weren’t so bad had vanished by April 1931. In Library Notes, Rankin wrote that the City helped 30,000 families in February, an increase of 60% over 1930. “Estimates indicate that 750,000 persons, ordinarily employed in gainful occupations are now without jobs.” The $8 million in funding for wages paid to workers on public works jobs had been spent. The State Legislature appropriated $10 million for wages and the Board of Aldermen approved $2 million in revenue bonds to be used for supplies and labor on public improvements and in public institutions—on such public work as will be of permanent value but which the City would not now perform except for the present unemployment emergency.”

A report in the Municipal Library’s vertical files written by economist Edna Lonigan for the Welfare Council of New York City issued in 1931 analyzed the number of unemployed New Yorkers by Occupational Groups. She estimated that 25% of waiters, 20% of musicians, 15% of deliverymen, 50% of longshoreman, 10% of telegraph operators and 33% of organized construction workers, among other occupations, were unemployed in December 1930. A memo from the Welfare Commissioner cited census statistics in estimating that 640,000 New Yorkers were unemployed—more than 10% of the population.

“The conditions are so extreme…” Letter to Mayor Walker from Raymond Ingersoll, March 6, 1931. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

As the economy continued in a downward spiral, it became clear that the well-intentioned private welfare organizations and one-off City efforts could not keep up with the need. Rankin wrote, “The most pressing problem for every municipality at this time is unemployment.”

Message to the Legislature from Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt… proposing comprehensive plans for meeting the crisis in New York by State participation, 1931. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

In a move that foreshadowed elements of the New Deal, New York State Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt submitted several proposals to the New York State Legislature for enactment in August 1931. The package contained five bills. The first set up a temporary administration, appropriated $20 million to fund employment on State and local public works programs, permitted the money to be used for food, fuel and rent but prohibited using the money as direct relief. The second bill increased the personal income tax by 50% and authorized the Comptroller to offer bonds immediately in anticipation of the increased tax revenue. The third bill gave local governments the ability to issue three-year bonds to fund public works which would reduce unemployment. Bill Number Four established a five-day work week on all public works. And the final bill allocated funds to pay bonuses to soldiers as required by an earlier law. In the transmittal message Roosevelt wrote: “—upon the State falls the duty of protecting and sustaining those of its citizens who, through no fault of their own, find themselves in their old age unable to maintain life.

But the same rule applies to other conditions. In broad terms I assert that modern society, acting through its government, owes the definite obligation to prevent the starvation or the dire want of any of its fellow men and women who try to maintain themselves but cannot.”

Sounding familiar today, he assailed the federal government. “It is idle for us to speculate about actions which may be taken by the Federal Government…It is true that times may get better; it is true that the Federal Government may come forward with a definite construction program on a truly large scale; it is true that the Federal Government may adopt a well though out concrete policy which will start the wheels of industry moving and give to the farmer at least the cost of making his crop. The State of New York cannot wait for that. I face and you face and thirteen million people face the problem of providing immediate relief.”

Taylor testified on behalf of the City in support of the proposed legislation. In doing so, he praised New York City’s work and noted that the City’s experience was unrivalled by any other unit of government. Calling the Governor’s relief request “conservative rather than extreme” he forecast that the City would spend $37.9 million on relief in 1931 or approximately $648 million in today’s dollars.

List of contributions received in the Office of the Mayor during the month of February 1931. Mayor James J. Walker Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

The final report of the Mayor’s Official Committee described the money raised and disbursed between October 1930, and June 1932. In total, they collected $3, 124,345 and spent $2,930,566. The report noted that for each $1 spent, 99 cents “went to the needy.” The monies were used for direct payments to the needy as well as food, clothing and coal for heating.

Walker was brought down after an investigation and legislative hearings headed by Judge Samuel Seabury. In January 1932, Assistant to the Mayor Charles F. Kerrigan wrote an eleven-page letter to the State’s legislative leaders requesting them to cease funding the investigation. In closing he stated, “We are now engaged with all our might in trying to avert a great calamity in this city and this country. We have engaged men and women of the highest talents and public spirit to assist us. The $400,000 wasted on this Investigation would have provided for feeding 4,400 people daily since the investigation began. The $2,000 a day now being used would feed 4,400 starving men, women and children every day this winter. The taxpayers of the State and all local governments are now being burdened with heavy costs to relieve the widespread suffering and want… This Investigation should be halted at once, and the balance of the fund, if any remains should be returned to the State Treasury for the relief of the taxpayers and to meet a part of the mounting deficit of the State government.”

In 1932, the year Walker resigned, the American electorate voted Herbert Hoover out of office and elected FDR to lead the country. The resulting New Deal and partnership with eventual mayor LaGuardia transformed the country and the City.