The Thank You Parades

On July 7, 2021, New York City hosted the ultimate event symbolizing a job well-done—a ticker-tape parade—for hundreds of essential workers, medical personnel, first responders, and others who helped the city get through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ticker-tape parade for Major General William F. Dean, the hero of Taejon and prisoner of war for three years during the Korean War, October 26, 1953.“Get it out of your heads that I’m a hero. I’m not. I’m just a dog-faced solder,” Dean told reporters after being freed from captivity. New Yorkers disagreed and gave him a rousing ovation. Mayor’s Reception Committee Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

In recent decades, New Yorkers have happily celebrated home-town athletic team victories with ticker-tape parades. But looking back at the more than two hundred parades, during the past one hundred and fifty years, we see how the City has paid unique tribute to pioneers of air and space travel, heads of state, politicians, journalists, and even a virtuoso pianist. Although this week’s ‘thank you’ parade was a unique event, the City has previously held ticker tape parades to thank sailors for heroic rescues at sea, firefighters for their service, returning war veterans for their sacrifice, and one exceptional nurse, ‘the Angel of DienBienPhu’ for her courage in battle.

From 1919 to the present day, the mayor of New York City has decided who receives a ticker-tape parade and the Municipal Archives’ mayoral record collections tell the story of the city’s parade history.

There is no thrill quite like a ticker-tape parade. All along Broadway, from the Battery to City Hall, thousands of spectators crowd the sidewalks or look down from skyscraper windows. They cheer and shout and toss confetti in a shower that becomes a blizzard of shredded paper falling on the motorcade below. Flags, marching bands, and music herald the procession. At City Hall, the mayor presents the honored guest(s) with a proclamation, a medal, a scroll, or a key to the city.

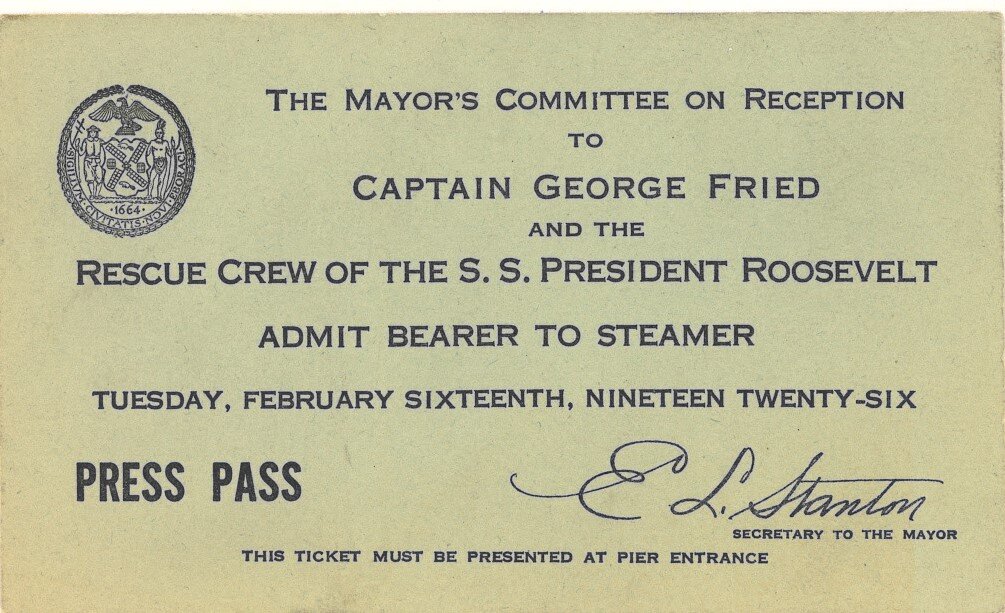

Press Pass, Captain George Fried reception, February 16, 1926. Mayor Walker Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The earliest parade recognizing exceptional service during an emergency took place on February 16, 1926. The event honored Captain George Fried and the crew of the steamship President Roosevelt for rescuing sailors aboard the British freighter Antinoe. Fried and his crew battled violent seas in a North Atlantic storm for four days to save all 25 men on the stricken ship.

Letter to Grover Whalen, Chairman, Mayor’s Reception Committee from the Pain’s Fireworks Company, regarding fireworks for the Captain George Fried ceremony. February 9, 1926. Mayor’s Reception Committee Collection. NYC Municipal Archives

Invitation from Mayor Walker to the Captain George Fried reception, January 28, 1929. Mayor Walker Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Almost unbelievably, three years later, in January 1929, Captain Fried was again involved in a dramatic sea rescue. This time, Fried and his crew of the Steamship America rescued 32 officers and seamen from the Italian freighter Florida. The City again thanked Fried and his sailors with a parade. In yet another twist, Harry Manning, the Chief Officer aboard the America enjoyed a second parade, two decades later. But this time it was for a less dramatic occasion. On July 18, 1952, Manning, by now Commodore of the S.S. United States, marched up Broadway with his crew to celebrate a new transatlantic speed record. Despite charges of a government boondoggle, the U.S. subsidized construction of the 2,000-passenger ocean liner on the premise that it could be converted to a troop ship in wartime. The luxurious superliner broke the transatlantic speed record previously held by the Queen Mary since 1938.

Mayor Impellitteri presents Medal of Honor and scroll for distinguished service to Commodore Harry Manning of the S. S. United States, July 18, 1952. City Hall. Mayor’s Reception Committee Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Replica bow of the S. S. Flying Enterprise installed on the steps of City Hall for Captain Henrik “Kurt” Carlsen ceremony, January 17, 1952. Mayor’s Reception Committee Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Press photographers on the pier await arrival of Captain Henrik “Kurt” Carlsen, Captain of the S.S. Flying Enterprise, January 17, 1952. Mayor’s Reception Committee Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Captain Fried and Commodore Manning and their respective crews were not the only examples of parades honoring dangerous maritime-related events. On January 16, 1952, Captain Henrik Carlsen received the city’s highest award for his heroic attempt to save his sinking ship, the S. S. Flying Enterprise. Carlsen spent twelve days aboard the doomed vessel to prevent it being claimed for salvage by another ship. He was finally persuaded to abandon ship just forty minutes before it sank off Lizard Point, the southernmost tip of England. The City built a model of the ship’s bow on the steps of City Hall to honor the captain, a native of Elsinore, Denmark, and resident of Woodbridge, New Jersey.

The City has recognized valor in other types of emergencies. In a ticker-tape parade on July 19, 1954, New Yorkers extended a warm welcome and thanks to Genevieve de Galard-Terraube, a nurse known as ‘the Angel of Dienbienphu’ for staying with wounded French soldiers in Vietnam. On May 7, 1954, after a 56-day siege, 49,000 soldiers of the communist Viet Minh surrounded and captured 13,000 French troops garrisoned at Dienbienphu, a military base in a remote corner of northwest Vietnam. This defeat signaled the end of French power in Indochina. Lt. Genevieve de Galard-Terraube, a nurse and pilot, was the only woman in the garrison. She spent 17 days as a prisoner, refusing to leave until the transfer of French wounded was complete. After her release, she confirmed that she had sent birthday greetings to Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh at the request of her captors because she feared refusal would endanger the wounded soldiers. She wrote a second time to thank him for her own liberation. Lt. de GalardTerraube was the third foreigner officially invited by Congress and the President to visit the U.S. (the others were the Marquis de Lafayette in 1824 and the Hungarian patriot Louis Kossuth in 1851).

Mayor Impellitteri awards Medals of Honor to 50 United Nations Servicemen wounded in the Korean War, October 29, 1951, City Hall. Mayor’s Reception Committee Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The City’s tradition of paying tribute to men and women of the U.S. military for their service and sacrifice extends back to the earliest ticker-tape parades. Post-war parades focused on victorious military leaders. Later parades lauded the rank and file. On June 2, 1950, the City staged a parade for the Fourth Maine Division Association Veterans of Pacific battles in World War II. Mayor William O’Dwyer’s papers include a transcript of his remarks at the City Hall ceremony following the parade: “Men of the Fourth Marine division – welcome to New York! We remember you well. We remember the bloody fighting in which you and your comrades, living and dead, fought your way across the Pacific at Kwajalein Atoll, Saipan, Tinian, and the black, smoking island of Iwo Jima. Those of us who were not with you from Camp Pendleton through the Central Pacific in the key battles against Japan cannot truly share your pride in the Fourth, since we did not share your battles. We cannot know your memories of names like Garapan, Mari Point, Tinian Town, and Suribachi. But we can be proud of you, and proud that you have chosen our City, the home of hundreds of your members, as your place of reunion. It is our great hope that old friendships will be renewed here, that your Association will be strengthened for future years, and that each of you will join the people of our City in a quiet prayer for the many, many Marines of the Fourth Division who suffered and died so far from the homes for which they fought. I cannot say to you too strongly that every one of the eight million of this greatest City welcomes you warmly and hopes that here you will find the best in all the things that make hospitality and friendship. Our City now belongs to you. God bless you all.”

Persian Gulf War Veterans ticker-tape parade, June 10, 1991. Mayor David Dinkins Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

“It’s time,” was the theme of the 1985 parade for veterans of the Vietnam War, and in June 1991, Persian Gulf War veterans and Korean War Veterans, were thanked with parades, on June 10, and June 25, respectively,

Program, Firemen’s Day ceremony at City Hall, April 15, 1955. Mayor Wagner Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

New York City workers have also had their days along the canyon of heroes. City firefighters have been honored with parades celebrating their service on multiple occasions. During the first, on March 31, 1954, 4,000 New York City firemen, marched up Broadway in observance of Firemen’s Day. Antique apparatus in the parade included an 1820 pump and a hose reel from 1810 pulled by firemen dressed in period uniforms. One year later, on April 15, 1955, 3,000 City firemen again celebrated the annual Firemen’s Day in a ticker-tape parade, and on August 30, 1956, 3,000 volunteer firefighters attending the 84th annual convention of New York State Firemen’s Association got a parade. The volunteer firemen were known as “Vamps,” after, the brightly colored socks (vamps) they had worn in bucket-passing days. It would be almost a decade before firefighters were again honored with a parade. On June 1,1965, 4,500 firemen celebrated the 100th anniversary of New York City’s first professional fire department in a ticker-tape parade. In 1865, the independent cities of Manhattan and Brooklyn supported 700 firefighters. By 1965, the Department had 13,186 men (still no women) and 282 firehouses in the five boroughs.

The 150th Anniversary of the laying of the cornerstone for City Hall included a “Pageant” at City Hall, May 26, 1953. Mayor Vincent Impellitteri Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Finally, the history of ticker-tape parades includes another unique event including city workers. On May 26, 1953, New York City Departments and units of the Armed services marched to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the laying of the cornerstone for City Hall. “Jenney,” a small donkey borrowed from the Bronx Zoo, hauled a replica of the cornerstone into place. Her performance was reported as “reluctant but adequate.”

We look forward to the addition of another marker on Broadway commemorating the ticker-tape parade of July 7, 2021, thanking the men and women who selflessly helped their fellow New Yorkers in a time of great peril.