The surprising but very welcome Supreme Court decision that lesbian, gay and transgender people are covered by the Civil Rights Law prohibiting discrimination in employment was long overdue. Many people may take for granted that New Yorkers are protected but there was a long, painful fight for those same rights in New York City. This 50th anniversary year celebrating the first gay pride parade is a good time to highlight the struggle

Now we refer to LGBTQ rights (Lesbian Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer) in order to be inclusive. In the 1970s and 1980s terminology evolved from homosexual rights to gay rights. It was a big change to name lesbian and gay rights. Transgender activists like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, leaders in the fight for equality, faced discrimination within their own movement.

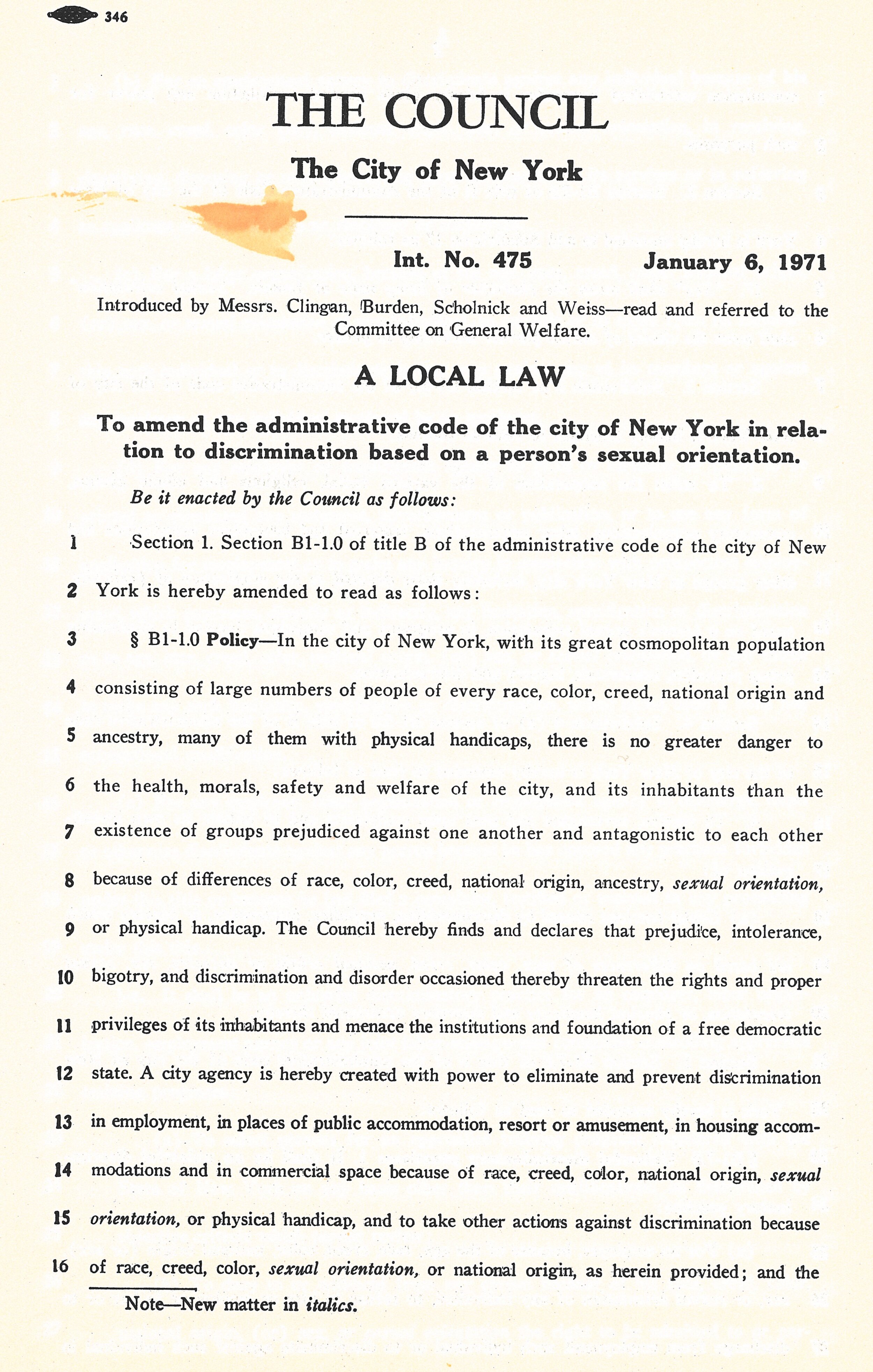

Intro. 475 of 1971. Mayor John V. Lindsay Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Municipal Library and Archives collections provide a trove of materials documenting the struggle to outlaw discrimination in the City. The first gay rights bill was introduced in the City Council in 1971 during the Lindsay Administration and assigned to the City Council’s General Welfare Committee. And there it lingered, rejected by committee members on four occasions. The New York City bill was simple—it amended the law that created the Commission on Human Rights by adding the words “sexual orientation” alongside the existing covered groups: race, creed, color, national origin or sex. It would have banned discrimination in housing, employment, places of public accommodation, resort or amusement and commercial space based on a person’s sexual orientation.

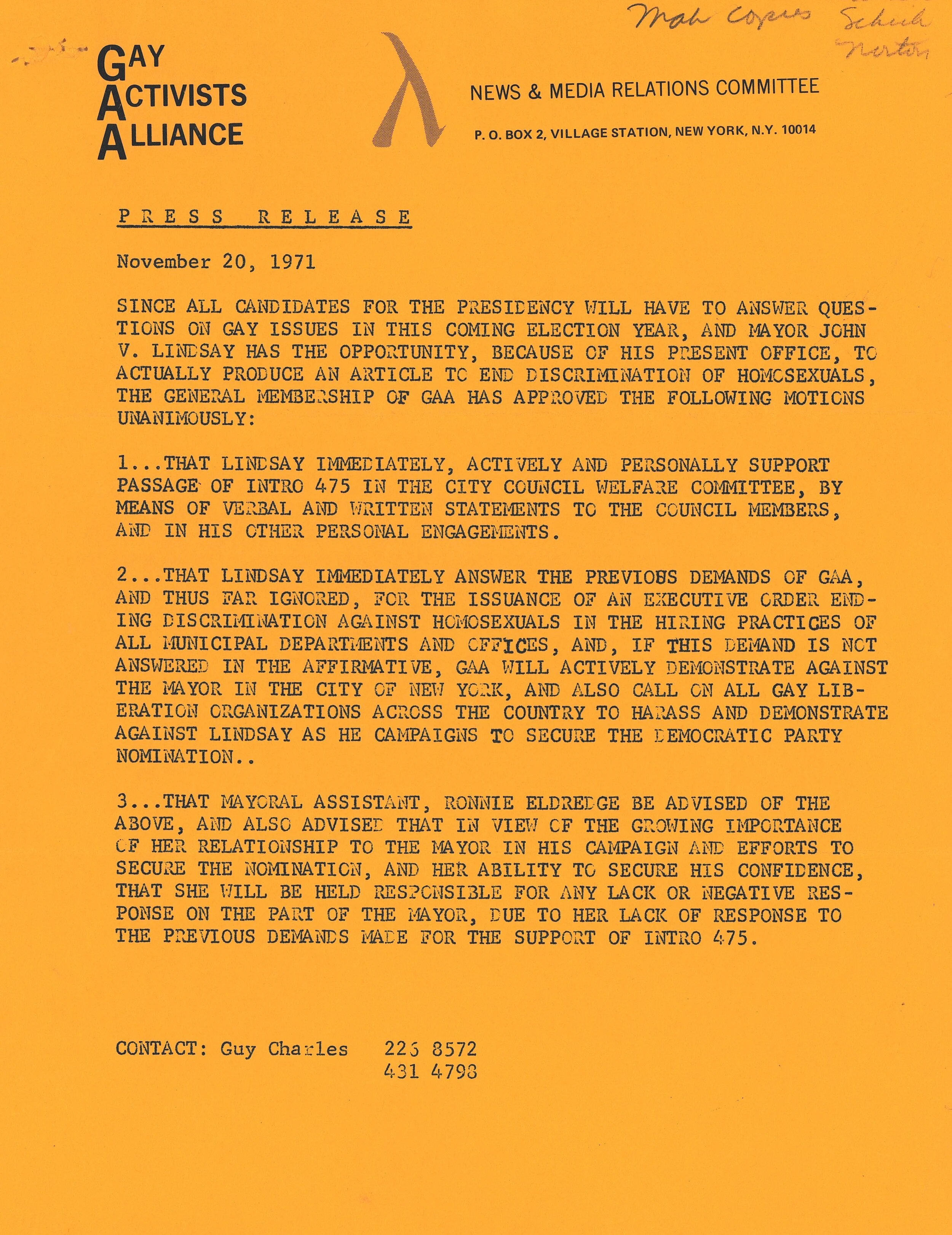

The Commission on Human Rights subject files in the collection of Mayor John Lindsay include a folder of documents received and sent by City officials. Correspondence in 1971 between members of The Mattachine Society and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) and City officials show the organizations were pushing the Mayor to both “actively and personally” support the gay rights bill and to issue an executive order ending discrimination against homosexuals in the City’s hiring practices. The GAA further threatened to activate gay liberation organizations across the country to “harass and demonstrate against Lindsay as he campaigns to secure the Democratic Party nomination.”

Gay Activists Alliance Press Release, November 20, 1971. Mayor John V. Lindsay Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

This, despite the Mayor’s earlier support in a letter to the sponsors of the gay rights bill commending them for their leadership in raising the issue and stating that it was appropriate for the City to “broaden its safeguards for citizens against all forms of arbitrary victimization.” The letter concluded by noting the Commission on Human Rights willingness to “lend assistance to passage of this useful legislation.”

In December 1971, Marvin Schick an assistant to the Mayor who, along with Ronnie Eldridge, was the point person on gay rights, testified on behalf of the administration in support of the gay rights bill. “We in the Administration believe that New York owes those of our citizens who happen to be homosexual no less than it owes the many others who have come to this city seeking tolerance, fairness and personal freedom. Our city should now take this logical step: to provide the protection of the law against the many abuses which homosexuals still encounter constantly.”

In January 1972, the GAA again pressed the administration to prohibit discrimination against gays in City municipal employment and expressed anger with the lack of progress. “We are appalled by the lip service the Mayor has given the issue” and threatened to hold him personally responsible if the gay rights bill failed. The pressure worked. In February, the Department of Personnel issued a policy bulletin that prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation in hiring and promoting within the municipal workforce. But, as the Association of the Bar of the City of New York noted in a committee report urging passage of the civil rights bill, the executive order “does not, of course, reach private employers.”

Department of Personnel, Personnel Policy and Procedure Bulletin, February 7, 1972. Mayor John V. Lindsay Subject Files. NYC Municipal Archives.

Later in a 1972 statement to the media, Mayor Lindsay expressed disappointment when the Council committee didn’t advance the bill. The action “further postpones the time when a person whose sexual preference may differ from the majority’s can seek equal justice from the City Commission on Human Rights if he or she has been discriminated against in obtaining or keeping a job or in obtaining or securing housing accommodations.” And that was that from the Lindsay administration.

By 1974, several municipalities and states had adopted gay civil rights laws, including Columbus, Minneapolis, Boulder, San Francisco, Berkeley, Seattle, Detroit, Ann Arbor, East Lansing, Washington and Toronto. One would think that New York City, home to the nation’s largest LGBTQ population would have been in the forefront. But, no.

In 1974, during the Beame administration, the gay rights bill finally was passed out of committee with seven of the eight members present supporting it, although some committee members did not show up to vote. In order to move the bill out of the committee an amendment clarifying that the definition of sexual orientation should not “be construed to bear upon the standards of attire or dress code.” Basically, excluding transgender people. Twenty of the Council’s 43 members co-sponsored the bill, meaning that only two additional council members were needed to vote in support for the bill to become law. Luminaries such as Eleanor Holmes Norton the head of the Commission on Human Rights, and then-candidate for Manhattan District Attorney, Robert Morgenthau testified in favor of the legislation. Former Mayor Wagner sent a statement of support and Mayor Abe Beame announced he would sign the civil rights bill into law.

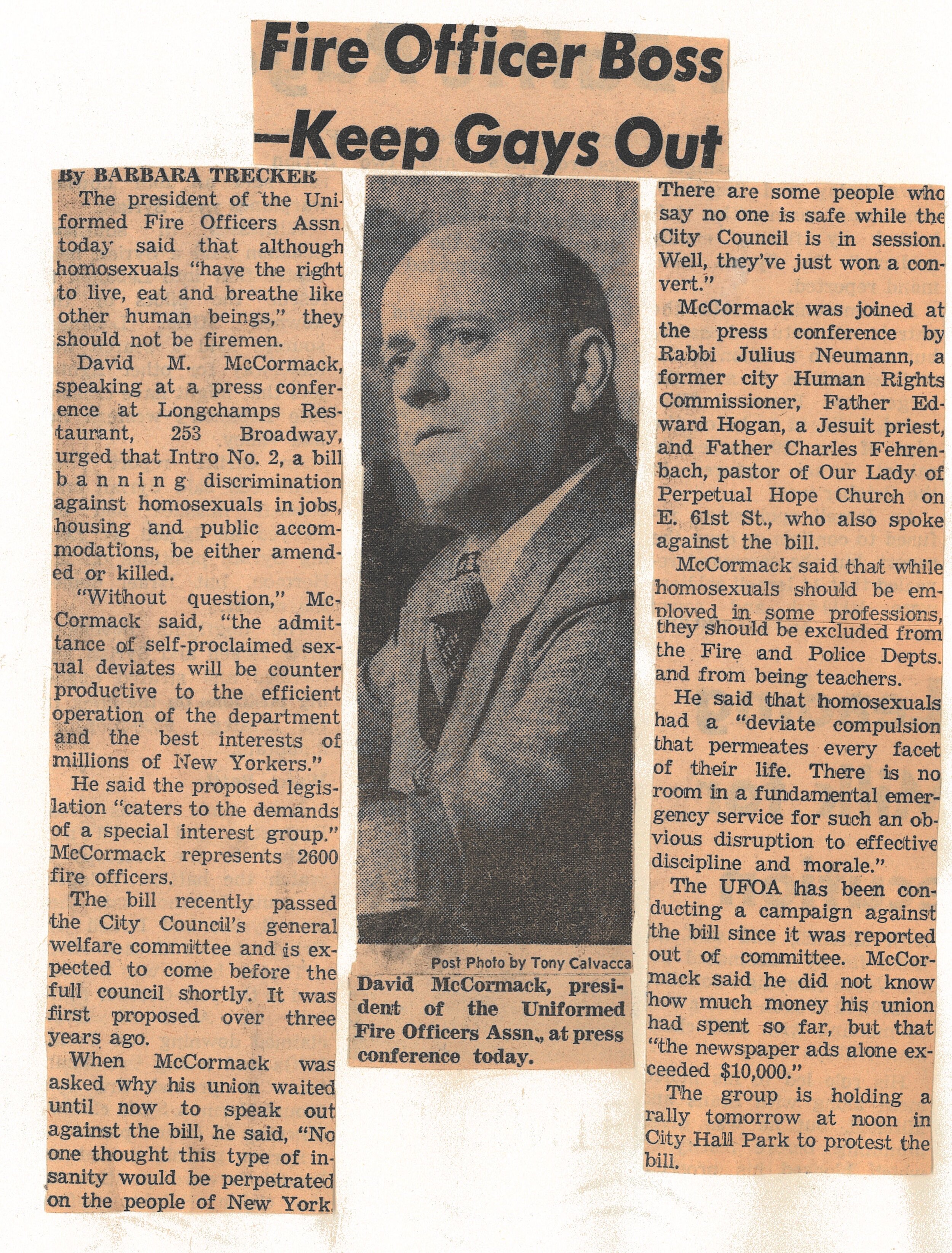

A done deal, right? Wrong. The opposition was lining up. The Uniformed Fire Officers Association led the charge, spending $10,000 ($52,000 in today’s dollars) in ads against the bill. The New York Times quotes a member of the Uniformed Fire Officers Association executive committee explaining the organization’s view “All members of the team have to be a man’s man.” The Daily News reported that Orthodox rabbis were denouncing the legislation. The New York Catholic Archdiocese mobilized against the bill and editorialized in the weekly paper distributed in parishes throughout the area that the bill was “a menace to family life.” In a front page editorial against the bill the editors claimed it would “Damage the true civil rights cause in this city and will endanger the freedom of every citizen to protect his family from a serious immoral influence.”

Clipping, Daily News, May 4, 1974. Municipal Library Vertical File, NYC Municipal Library.

Newspaper clipping, April 29, 1974. Municipal Library Vertical File, NYC Municipal Library.

Supporters included the American Civil Liberties Union, the Citizens Union, the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, the Gay Activist Alliance and the Ad Hoc Coalition of Gay Organizations. Surprisingly, the powerful county leaders, who typically instructed councilmembers on how to vote were split with the Brooklyn and Bronx leaders supporting the bill while the Queens leader opposed it.

This battle predated the internet and social media. Supporters and opponents instead relied on the U.S. Mail to air their views. It was estimated that council members were receiving 100 letters per day on the proposal. That was a lot considering that this was the era when the Council was compared negatively to a rubber stamp because a stamp left an impression.

By the time the bill came to the full Council, tensions were high. At the hearing, curses and epithets were shouted, hisses and boos as well as applause rained from the chamber balcony. The debate was brief but heated. The New York Times wrote that the Councilmembers praised it “as a simple civil rights measure and denounced it as an attempt to endorse a deviant live style.”

A Catholic priest, Louis Gigante who also was a Councilmember rejected the Archdiocese guidance. He explained that the bill said, “Give them the right to live. With all my Christian conscience, my priesthood and as a human being, I emphatically vote, yes.”

Harlem Councilmember Frederick E. Samuel, one of only four black members, said he’d been warned that a yes vote would be political suicide. “As a black legislator, I say to you then that I will enter my political graveyard with a deep sense of pride.”

The bill was defeated in a vote of 22 to 19, with two abstentions. And year-after-year the civil rights bill was reintroduced, referred to the General Welfare Committee. Eight times, sponsors tried to move it to a full Council vote and failed. Finally, in 1986, the bill became law. That is another chapter in the long LGBTQ battle for equal rights and the subject of a future blog.