New Yorkers have been celebrating Independence Day since July 4, 1777. Or, have they? Municipal Archives collections are extensive and said to provide documentation on any topic in New York City history. However, there is one notable gap in the holdings. Municipal government was suspended during the period of British occupation from 1776, until the last troops left from the Battery on November 25, 1783. The existence and/or whereabouts of any administrative records for that period has been the subject of speculation ever since. For the Record examined the subject in The Missing Common Council Records of the Revolutionary War.

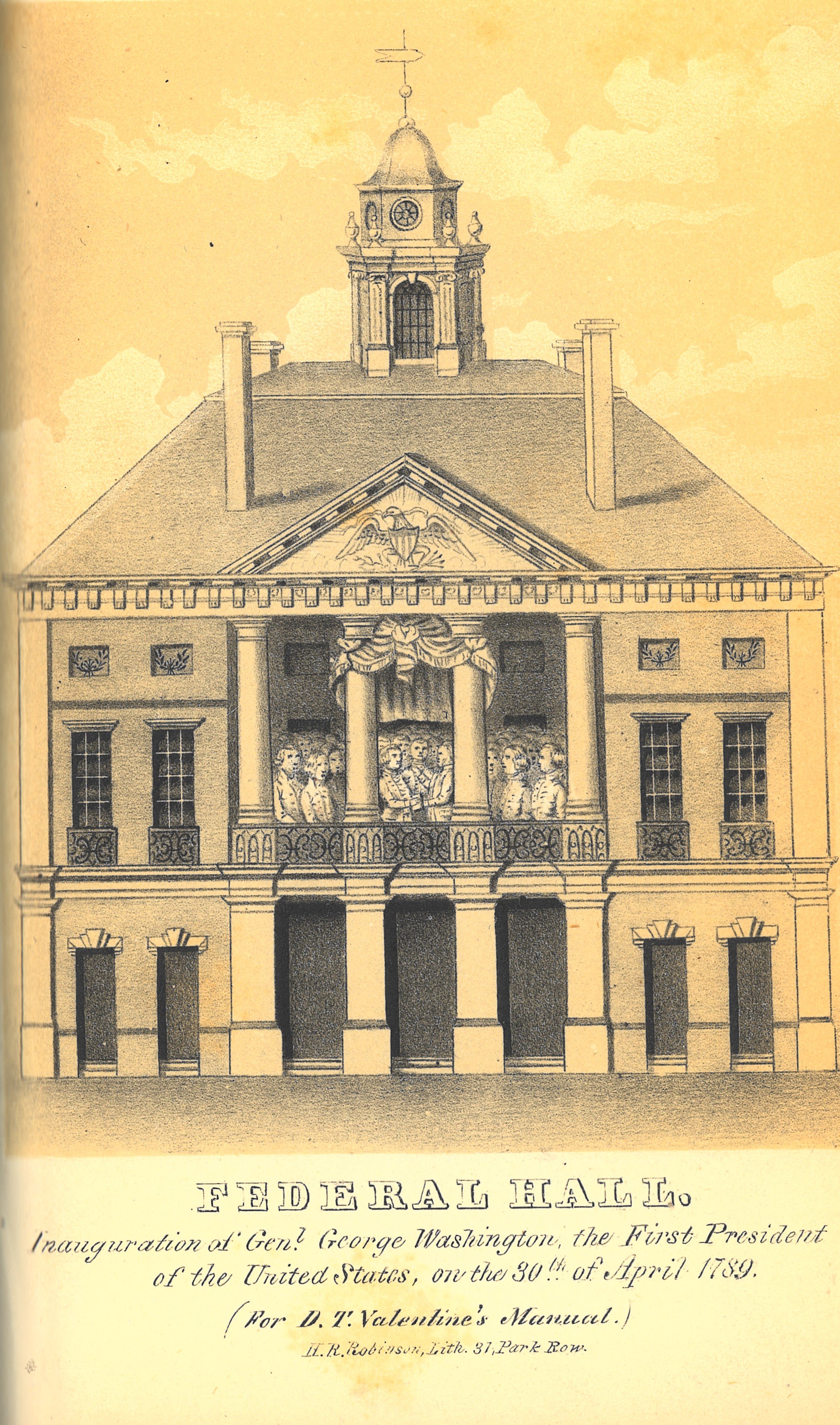

City Hall, Valentine’s Manual, 1852. NYC Municipal Archives

Researchers are not entirely without information about the city during the first decades of the new republic. The six-volume Iconography of Manhattan Island, by Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, helps fill the documentation gap. Stokes relied on newspaper accounts and other sources, as well as the Minutes of the Common Council, to write a daily chronicle of key events in city history from 1498 to 1909.

Federal Hall, 1789, Valentine’s Manual 1849. NYC Municipal Archives

The Municipal Library collection includes the Iconography and looking at entries during the Revolutionary War period reveals that Philadelphia celebrated the first “Anniversary of the Independence of the United States of America,” in 1777. It is possible to imagine that at least some New Yorkers also managed to celebrate Independence Day, quietly, but Stokes makes no mention of festivities in New York City during the occupation.

Municipal government reconstituted in 1784, and the re-convened Common Council held its first meeting on February 10. When municipal government restarted, so too, did record-keeping in the form of the Minutes of the Common Council. The Minutes and the related series, Common Council papers, are two of the most essential collections in the Municipal Archives.

There is a useful cumulative index to Minutes of the Common Council covering the period 1784 through 1832. Reviewing the entries for “Fourth of July,” shows the first mention of a celebration in 1785: “…That Alderman Broome & Bayard & Mr. Lawrence and Mr. Ten Eyck be a Committee to report the Measures proper to be taken by this Corporation on the Fourth of July; being the 9th anniversary of the Independence of this State.” (Common Council Minutes, 22 June 1785.)

The Committee to Report the proper manner of celebrating the 4th of July next (partial text), Minutes of the Common Council, June 21, 1796. NYC Municipal Archives

The Council established similar committees, on an annual basis, through at least the first several decades of the 19th century. In 1786, the appointed committee reported to the Council on the arrangements for Independence Day: “That at sunrise the day be announced by a display of colors, a discharge of 13 Cannon & the ringing of all the public Bells for one Hour. That at 12 O’clock there be a Procession of this Board & other public Officers & the Citizens from the City Hall down Broad Street & through Queens Street to the Residences of their Excellencies the Governor & the President of the United States and thence by way of Beekman Street to the City Tavern where a Collation be provided…” (Common Council Minutes, 28 June 1786.)

Warrant to Daniel Phoenix, Treasurer, for payment of twelve Pounds for the ringing of the bells on the 4th of July, 1795. Common Council papers. NYC Municipal Archives.

Warrant to Daniel Phoenix, Treasurer, for payment of twenty-five Pounds for illuminations and fireworks on the 4th of July, 1795. Common Council papers. NYC Municipal Archives.

In 1789, according to Stokes, “The presence of [President George] Washington in New York makes the celebration of Independence Day especially noteworthy.” Unfortunately, as Stokes reports, Washington had been suffering an illness which “…Deprived the troops of the honor and satisfaction of being reviewed by him in the field.” But later in the day “…they passed the house of the President… who appeared at his door in a suit of regimentals, and was saluted by the troops as they passed.” In the afternoon, a concert in St. Paul’s church was “honored by the presence of the First Lady and Family of the President, his indisposition (the inconvenience of which thanks be to Heaven, are nearly surmounted) prevents his personal attendance.”

The related series, Common Council papers, also provides information about Independence Day celebrations. The series consists of documents written by or presented to the Council. The date span of the entire series is from 1670 to 1934. However, the material after 1870 consists primarily of resolutions with little supporting documentation. From 1800 to 1831, the documents are separated by year into folders generally pertaining to the standing and special committees created by the Council, e.g. Arts, Sciences & Schools, Charity & Almshouse, Fire & Water, Lamps & Gas, Police, Watch, Prison, Streets, Wharves, etc. The folders are arranged alphabetically. With funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Municipal Archives processed and microfilmed the Common Council papers.

Invoice for payment for punch, grogg, wine, etc., July 4, 1793. Common Council papers. NYC Municipal Archives

The papers helpfully include warrants for payment to vendors who supplied services for Fourth of July celebrations. In 1795, Captain Bauman’s bill for “…illuminations & fireworks… on the celebration of the late anniversary of American Independence,” amounted to twenty-five pounds.

In 1793, John Simmons’ bill for four large bowls of punch, nine bowls of grog, thirty bottles of wine, plus coffee, crackers, etc. came to twenty-six pounds, nine shillings and six pence. What is less clear is who consumed the beverages. Perhaps this is typical of the “collation” referred to in the 1786 Minutes. In any case we will assume they enjoyed the celebration.

From For the Record, wishing everyone a happy Fourth of July!