Baseball fans know that the Yankees v. Dodgers games this week were not the first time the two faced off in the World Series. In 1941, the Yankees vanquished the Dodgers four games to one. At their next meeting in 1947, the Yankees won again, four games to three. The two teams dueled ten more times, most recently in 1981, when the Dodgers won the trophy four games to two.

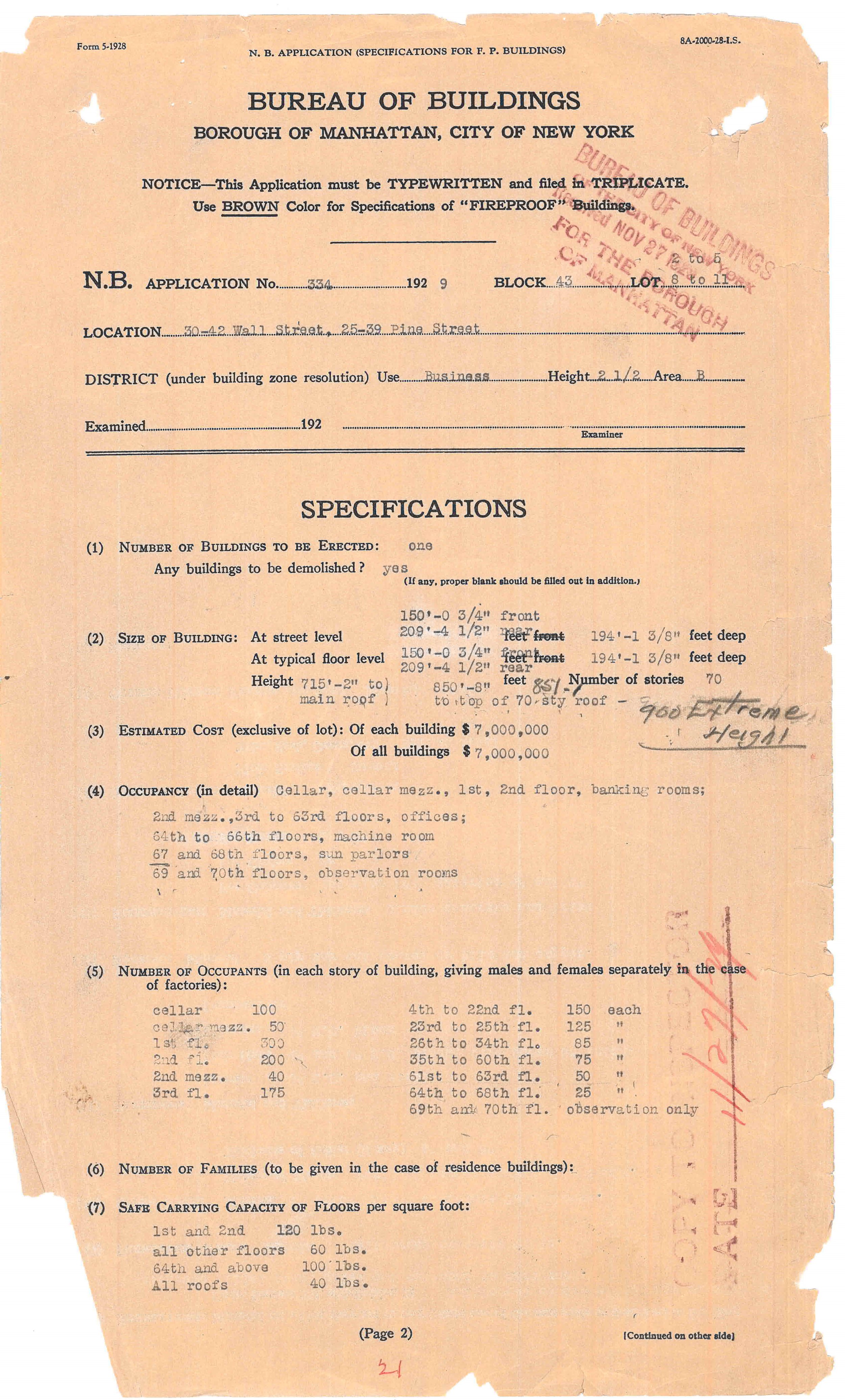

Double Header, April 14, 1943, Poster. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Perhaps less well-remembered is a pre-season tournament with the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants. It took place on April 15, 1943, as a benefit for the Civilian Defense Volunteer Office. At that time all three teams were New York-based—the Yankees in The Bronx, the Giants at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, and the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, Brooklyn. In the benefit match, the Yankees battled the Dodgers in the first game; the Giants played the winner in the second.

President Roosevelt established the Office of Civilian Defense on May 21, 1941, and appointed Mayor LaGuardia as its National Director. LaGuardia held this position until the end of World War II. The Office was tasked with alerting and educating the public about civilian defense, organizing volunteer groups, and training fire protection and bomb disposal units in anticipation of damage caused by air raids.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s records provide context for the benefit tournament. His collection is organized into twenty-one series such as departmental, general and subject files. In addition, there are two series, the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD), and the related Office of Civilian Defense Volunteer Office (CDVO), relevant to research on the topic.

The OCD series includes a folder of documents concerning the benefit game. One informative item is a draft statement from the Mayor appealing to all New Yorkers to support the CDVO by buying tickets to the baseball series to be played at Yankee Stadium starting at one p.m. on April 15, 1943 The statement quotes LaGuardia: “CDVO is doing a great job... and deserves the support of every New Yorker. Men and women volunteers are giving freely of their time and energies in undertaking the many home-front tasks occasioned by the war. CDVO up to now has been run on voluntary contributions but money is needed urgently to carry on the work.”

The folder also contains carbon copies of letters LaGuardia sent to heads of City agencies requesting the release of designated employees to help with ticket sales. The only blip in the preparations appears to have been in the New York City Housing Authority. A telegram to the Mayor from “Painters NYC HA,” dated April 13, just two days before the tournament explained the situation: “Please be informed that painters of NYC Housing Authority have been refused permission to attend baseball game April 15 while office force of same authority have been granted same permission. Strongly protest this flagrant discrimination.” The next day, April 14, LaGuardia received a letter from Edmond Borgia Butler, Chairman of the New York Housing Authority: “As you know, our painters and other maintenance employees work on a rigid schedule, which must be maintained if the necessary services are to be supplied tenants in our projects. Except for these employees and the administrative staff, all other employees were permitted to be absent to attend the baseball.”

Telegram, April 13, 1943. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia Collection. NYC Municipal Archives

The file does not include LaGuardia’s response to these missives.

Whether or not Housing Authority painters attended the game may never be known, but 35,301 spectators did witness the tournament, according to the New York Times. The Times story related how the Brooklyn team vanquished the Yankees, six to one, and then went on to defeat the Giants, one to zero. In the words of Times reporter John Drebinger: “In an era of considerable scarcity the Dodgers simply had too much of everything yesterday as they crowned themselves the so-called “mythical” baseball champions of Greater New York by polishing off both the Yankees and Giants in the CDVO double-header at the Stadium before a gathering of 35,301 frostbitten but highly enthusiastic onlookers.”

In his statement Mayor LaGuardia added “The Presidents of the Yankees, Dodgers, and Giants ball-clubs have generously donated the net proceeds of these two games to CDVO and it is up to all of us to make April 14th the greatest day in baseball history.”